Acousmatic music is a form of electroacoustic music that takes sounds found in the world around us, as a significant form of sound material. With the use of reduced listening (Shaeffer 1960) we deliberately ignore the source of the sounds within the composition and focus on the sonic properties, timbre and spectre of the sounds themselves. But what if a composer is set limitations on the sound objects they can use? And particularly on a composer who is composing an acousmatic piece?

For this project I aimed to compose a full acousmatic piece, using the limitations on my sound objects. This means I collected, processed and used sound objects that have a strong attack, but little to no decay ( i.e sound objects that are 1 to 2 second long). This sound material was collected from my home and workplace. I then aimed to combine these together to create a full 7 minute (give or take) piece showcasing the sounds sonic properties, while documenting the benefits and setbacks I had while composing this piece with the limitations in place. I then also aimed to use compositional techniques such as the use of spatialisation and certain aesthetics that I have researched throughout this progress. By the end of this project I hope to have collected enough information to answer to my research question, ‘In what ways does the use of limited sound objects hinder or benefit a composer?’.

Why did I chose to create an Acousmatic composition?

Even before I found myself studying Music, Media & Performance Technology, I was highly interested in music composition and the techniques used in doing so. Since I was brought up on a classical and Irish traditional basis of music, I was not exposed to the works of electroacoustic composers until I entered into University. During a semester in the module ‘Digital Arts 1’, I was acquainted to works such as ‘Imaginary Landscapes’ by John Cage, in which Cage showcases sounds from turntables, records of constant and variable frequency and percussion instruments. Intrigued by the use of sound in such an ‘unstructured’ way that I was not used to hearing sparked my interest in sonic art and the use of sound in such a way - to be appreciated for its sonic properties rather than used in a classical manner.

This interest soon led to the choice to pursue Fixed-Medium Composition as part of my Final Year Project. Before officially submitting my choice of topic, I researched the different compositions of fixed media, electroacoustic music and subsequently, acousmatic music. I listened to many artists, including Denis Smalley, Jonty Harrison, Natasha Barrett, Manuella Blackburn and of course, Pierre Schaeffer, who was the first to use the term acousmatique to define the listening experience of musique concrète.

A significant composer to mention, and who aided in influencing me in my choice of research question was Manuella Blackburn, an electroacoustic music composer, who specializes in acousmatic music . In her piece ‘Switched On’ (Formes Audibles) she creates an imaginary landscape that is somewhat ‘ magical’ to hear, through fixed medium composition. In this piece she explores sounds she collected over a period of time from around her home and work office. The sounds comprise of switches, clicks of electrical appliances, and an old TV being switched on, giving it its title. When turned on, the old television created a sequence of sounds from the static and frequencies from it starting up. From this piece, I was inspired by the short length of most of the sounds she had used, but was able to manipulate these sounds to create an intriguing and magical piece. I then decided that It would be both interesting and informative to set myself with similar limitations within the sound objects I could use in my own piece - short and sudden.

A significant composer to mention, and who aided in influencing me in my choice of research question was Manuella Blackburn, an electroacoustic music composer, who specializes in acousmatic music . In her piece ‘Switched On’ (Formes Audibles) she creates an imaginary landscape that is somewhat ‘ magical’ to hear, through fixed medium composition. In this piece she explores sounds she collected over a period of time from around her home and work office. The sounds comprise of switches, clicks of electrical appliances, and an old TV being switched on, giving it its title. When turned on, the old television created a sequence of sounds from the static and frequencies from it starting up. From this piece, I was inspired by the short length of most of the sounds she had used, but was able to manipulate these sounds to create an intriguing and magical piece. I then decided that It would be both interesting and informative to set myself with similar limitations within the sound objects I could use in my own piece - short and sudden.

Collecting Sound Material

As soon as I had decided on using limited sound objects for my piece, I started my search for sound material at home and a the workplace that fitted into this limitation. Of course I had already mentally made a list many sounds that fitted into this description. Some included an old switch in one of the bathrooms located in my house, that had a lower undertone than a normal lightswitch. From this I went to locks on doors, including my front door lock, which almost bounces into place when used.

It was important for me make a list of sounds I wanted to recorded before I was to rent out the H6 Zoom, so I had time to evaluate these sounds before my renting time was up.

In the first round of recordings, I collected a small range of sounds. These included switches, locks, finger clicks, lighter clicks. After evaluating these, and showing them to my supervisor, it seemed I was missing out on some potential sounds that fitted my limitations. On my second round of recording, I collected sounds that had a bit more ‘colour’ to them. These including cans opening, spraying of a spray can and hitting hollow objects with another object. Soon I had collected up to 30 sounds I was happy with.

In the first round of recordings, I collected a small range of sounds. These included switches, locks, finger clicks, lighter clicks. After evaluating these, and showing them to my supervisor, it seemed I was missing out on some potential sounds that fitted my limitations. On my second round of recording, I collected sounds that had a bit more ‘colour’ to them. These including cans opening, spraying of a spray can and hitting hollow objects with another object. Soon I had collected up to 30 sounds I was happy with.

Of course, there was some setbacks. In the first collection of recordings I had, many had too much feedback or background noise, and could not be used. Since I could be amplifying certain frequencies within the sounds, the feedback would become more of an issue. On one occasion, I did not notice of the slight feedback until I was halfway editing a sound object, and had to wait two weeks to re-record this sound.

Sound File Organisation

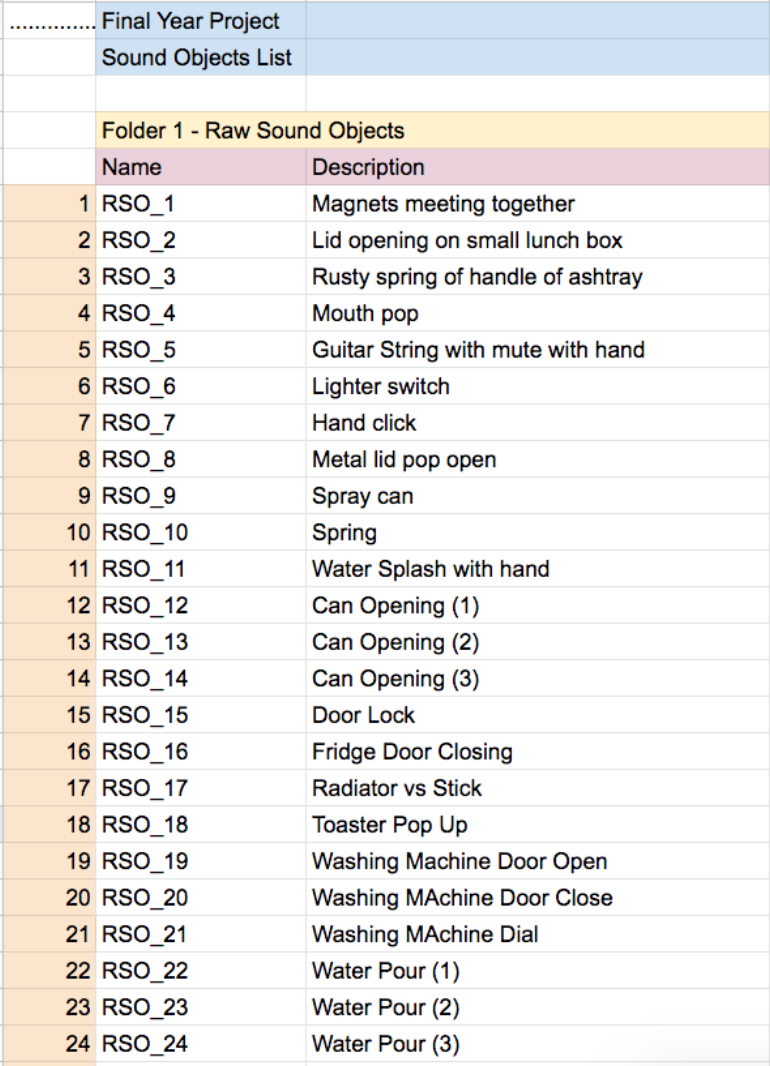

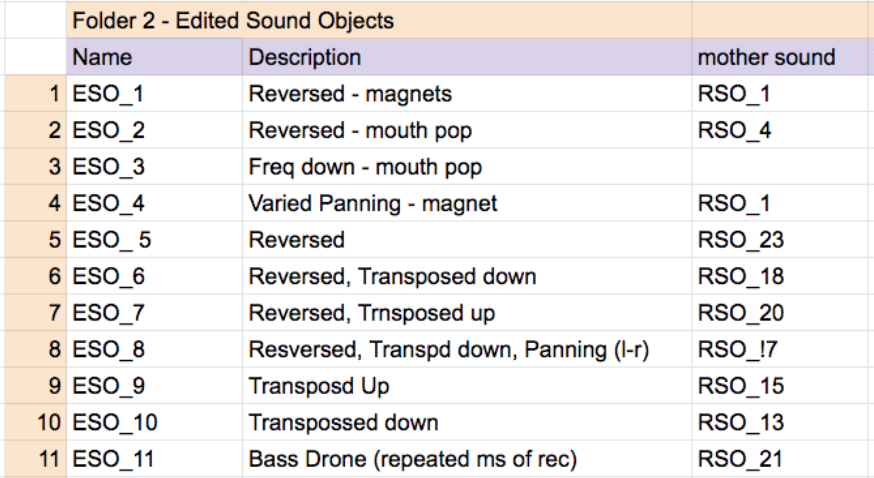

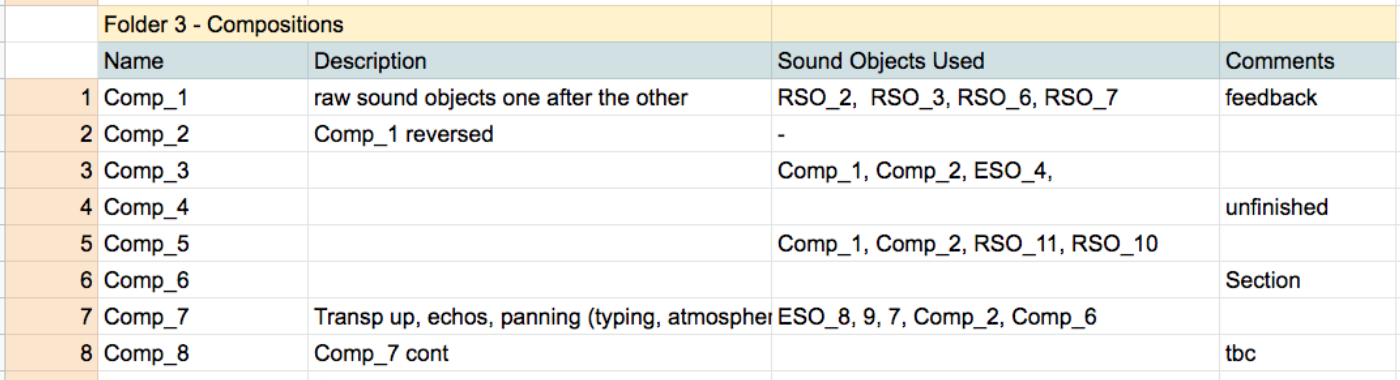

With the amount of of sound files building up, from both recording, and producing from processing new sounds, I felt the need to create a sound filing system that helped me manage my sounds and time better. I knew that once I started using my files in larger compositions and they became beyond recognition, I would need a system to track back to the original files for future reference. I decided to create an excel spreadsheet to keep notes on all my sound files. I made three different sections:

Raw Sound Objects (RSO) - the original sounds I recorded

Edited Sound Objects (EDO) - sounds created by processing RSO’s

Compositions (Comp) - short compositions consisting of many sounds (RSO & ESO)

All of the listed sounds were then organised within folders, for easy access and use.

Composing

I began my compositional process by first chosening what software would best suit my piece. I had first tried processing sound using simple high pass filters on MAXmsp, but found they over processed the sounds. On top of that, It was all generated out of much of my control, and I felt I needed full control over how the sound would be used and placed within the composition, and I didn’t have the time to teach myself this. That left with me choosing over Ableton and Pro Tools. For me, Ableton was a clear choice. I was familiar with processing sounds from past projects on Ableton, but for me, Pro Tools seemed more of a tool for mixing and mastering traditional music.Of course, I did used Pro Tools in the end to help me finish mastering my full piece.

Once I had my Ableton Live session open, I was faced with the lengthly amounts of audio effects at my disposal. At first I decided to stick to Shaeffers original techniques, like reversing and speed change. Unlike with tape, when it must be cut up and joined back together, modern software allows for quick and easy processing of sound. In Ableton Live, reversing and frequency change can be done instantly.

Analysis

Notation has gradually developed into ever more sophisticated and complicated forms. Notation helps one to understand music in an easier way through visual representations, reducing it into simpler elements. In classical music notation, a lot can be understood from how its written, and due to the endless guides for musicians to follow. People who can read this musical score can gain a lot from it, knowing its key, instrument, rhythm etc, and could even somewhat create an image in one’s head on how it will sound. (Pasoulas, 2019)

In acousmatic music, there is no score. Usually, some sort of notation, if any, is only created a after the piece is complete. But even with that, a lot of data is lost when one attempts to note down an acousmatic piece. In acousmatic music, or electroacoustic music in general, a lot of data cannot be represented in graphical notation form. Through computer generated representations of sound, we are given such as the waveform and the songram. It hasn’t been until the last century that graphical notation has become more used by composers, such as Denis Smalley, in order to document and present his pieces.

When it comes to acousmatic compositions, having some form of analysis on the piece is useful when it comes to future reference. How composers conceive musical content and form – their aims, models, systems, techniques, and structural plans – is not the same as what listeners perceive in that same (Smalley, 1997). Although some data can’t be represented, it is still useful for understanding the piece to some extent.There are many ways one can analysis or represent an acousmatic piece. These include:

Waveform

A waveform is an image that represents an audio signal or recording. It shows the movement of amplitude over a certain amount of time. The amplitude of the signal is measured vertically on the y-axis, while time is measured horizontally along the x-axis. Below I have two examples of waveforms taken from my own Ableton Live session.

Fig X: example of waveforms (taken from my compositions Ableton Live session).

Sonogram

A sonogram is a 2D graphical representation of an audio signal or recording. Time is represented along the x-axis (horizontally), amplitude is represented on along the y-axis (vertically), and frequency is represented by the colour intensity (white/yellow being low frequency and darker colours being high frequency). Having three characteristics of the sound represented on one graph, gives it its two dimensions. Below is an example (FIGx) of a sonogram, with a waveform underneath, to help to further explain how it works.

Fig x: example of a sonogram, with waveform below it for reference.

Drawn Graphic Interpretation

Lastly we have drawn graphic interpretations - or simply - graphical score. I discovered these through Denis Smalley's work, and was impressed by his ability to create an accurate representation of sound, and more impressively, acousmatic sound. Below I have included an image (Smalley, 2019) showing a section of Smalley’s graphic score for ‘Vortex’.

FigX: Graphical score of Denis Smalley’s ‘Vortex’.

Smalley's graphical score was created using visual representation that is personally create by him. Although other composers could create a visual similar score, there are no defined rules for composers to follow when making graphical scores. That said, we can see some representation of different sound shapes.

Conclusion & Findings

In conclusion, this paper has reflected answers to my research question, in correlation with my composition. Along with personal skills, I have gained a lot from this project and anticipate that listeners and viewers of my composition and paper will also do so.

When an acousmatic composer is faced with restrictions or limitations, they are forced to think in a way that might not normally do so. This opens up a path to new discoveries and techniques that they as a composer have never personally used or even new discoveries in the acousmatic world itself. Personally, I found that being faced with limitations on top of being completely new to composing acousmatic music, I was slightly out of my comfort zone, and struggled at first when it came to beginning the composition. With endless amounts of information and compositions available to me I was able to soon find a starting point. Inspired by composers and their processes and philosophies, processing sounds was easier and easier the more I researched and put it into practice.

When an acousmatic composer is faced with restrictions or limitations, they are forced to think in a way that might not normally do so. This opens up a path to new discoveries and techniques that they as a composer have never personally used or even new discoveries in the acousmatic world itself. Personally, I found that being faced with limitations on top of being completely new to composing acousmatic music, I was slightly out of my comfort zone, and struggled at first when it came to beginning the composition. With endless amounts of information and compositions available to me I was able to soon find a starting point. Inspired by composers and their processes and philosophies, processing sounds was easier and easier the more I researched and put it into practice.

Since I had such short sounds to work with, I was ‘forced’ to spend time in little details and focusing on the exact placement of each sound one after the other. In (PART WHERE DOOR LOCK IS UP AND DOWN) of the composition, I tested out variable patterns that felt natural to the ear as the sound changed frequency, and became satisfying to hear. The fact that the limitations forced me to be so precise, helped in the development of the style and aesthetic I used, and so it worked in my favour as a composer.

Of course, there was some drawbacks to having limitations set in place. There’s no doubt hat when limitations are put on a composer, that they are then restricted to using certain processes and techniques. For me, I found myself using roundabout ways to create a certain sound. For example, for the pattern tapping sound (3.25 in composition), I had to loop the sound over and over to get the pattern. If I had no limitations, I could have simple created the pattern in the original sound recording, and saved some time on processing it afterwards. This can be said for a majority of the work I put into composing this piece. Since I was working with such short sounds, I had to do double the processing in order to create a substantial composition.